Birb Cam

Why?

I had no idea how many critters visited my balcony planter box until I started working from home last March. I would sit nearby with my laptop and watch chickadees and sparrows fly in and out, magpies wander across the railing, and even a squirrel that decided to start caching treats in the soil. At first, I was content to watch them come and go. Eventually, I started to wonder how often they were visiting without me even noticing. Then it occurred to me: I didn’t need to wonder, I could know!

How?

- OpenCV

- Fast.ai

- Google Cloud Functions

- A Raspberry Pi 4

- A really old and really bad USB webcam

- Flask

Why OpenCV?

I needed some way to quickly detect changing pixels and planned to use Robust PCA, a technique that I learned about in a master’s degree course on high dimensional data analysis. Robust PCA is a very cool technique that can separate each frame from a video into a static background matrix, a foreground matrix with the pixels that have changed, and a noise matrix. The only issue is that Robust PCA is a little slow to be used in real-time, and would I would need to do some thinking to get it working online in a frame-by-frame manner.

Meanwhile, OpenCV has a good selection of background subtraction models that do what I’m looking for. They also have the benefit of being built by experts, so they run well and run fast. No need to reinvent the wheel here!

A minimal example of the OpenCV Background subtraction model used is:

import cv2 as cv

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from scipy.signal import medfilt2d

# Open webcam

capture = cv.VideoCapture(0)

capture.set(cv.CAP_PROP_FPS, 1)

# Set up Background Subtraction Model (bgsub)

backSub = cv.createBackgroundSubtractorMOG2()

# Bgsub and median filtering parameters

mask_thresh = 255

kernel_size = 25

lr = 0.05

burn_in = 30

i = 0

# Loop through the frames from the webcam

while True:

ret, frame = capture.read()

fgMask = backSub.apply(frame, learningRate=lr)

# Avoid early false positives

if i < burn_in:

i += 1

continue

# Threshold mask - detect change

fgMaskMedian = medfilt2d(fgMask, kernel_size)

# Plot the image and changing pixels

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3)

frame = cv.cvtColor(frame, cv.COLOR_BGR2RGB)

axs[0].imshow(frame)

axs[1].imshow(fgMask)

axs[2].imshow(fgMaskMedian)

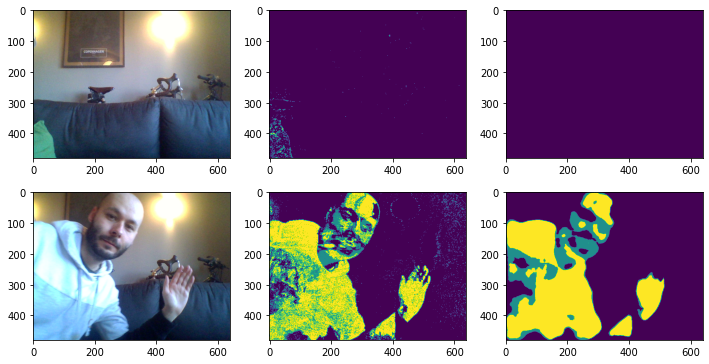

plt.show()This code produces the following plots, but with critters instead of me:

Why Fast.ai?

In the past few years, I have heard about fast.ai and unjustly wrote it off as just some simple Kaggle computer vision competition non-sense. Oh, how wrong I was. I have since watched many of the lesson videos and even read their new book. Fast.ai makes using deep learning for common computer vision tasks so easy without depriving you of the flexibility to do what you want with the models and training process. It’s very similar to how Keras makes working with TensorFlow models more approachable and more productive.

Jeremy Howard and the fast.ai team are all about transfer learning and disabused me of the notion that you still need a fair amount of data to do much with it. You can often get shockingly good results with only a few dozen examples of each class. Getting up and running with a ResNet model pre-trained on ImageNet only requires a few lines of Python.

Then there are the data loaders, utility functions, and augmentations that handle the data management and training loop details you probably don’t need to write out yet again.

I’m a fast.ai convert now. To motivate this point, check out this minimal example of training a Birb Cam model:

from fastai.vision.all import *

import pandas as pd

# Table of labels: columns "fname" and "labels"

df = pd.read_csv("labels.csv")

path = Path("birbcam/data/")

# Create our data loader for training and validation, with automatic image

# resizing, cropping, and data augmentation (flips, rotation, skew, etc.).

dls = ImageDataLoaders.from_df(df, path, folder='training', label_delim=',',

item_tfms=Resize(224),

batch_tfms=aug_transforms(size=224))

# Create our model, with pre-trained ResNet 34 weights

learn = cnn_learner(dls, resnet34, metrics=partial(accuracy_multi, thresh=0.5))

# Find a good learning rate to use while training

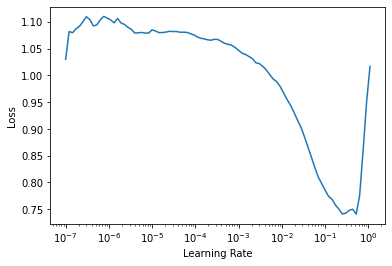

learn.lr_find()

# Train our model using mixup, a further augmentation that blends images and

# labels together to create hybrid images. Often improves performance

mixup = MixUp(1.)

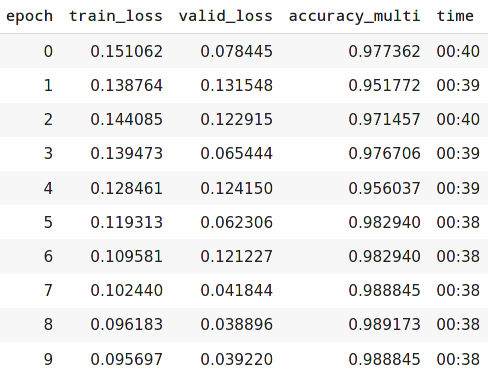

learn.fine_tune(10, 3e-2, cbs=mixup)

# Export the model for use in production

learn.export("birbcam_prod.pkl")It’s concise, with only 26 lines total, 10 of which are actual code if you throw out the white space and comments. Fast.ai provides the excellent learning rate finder tool to find the best learning rate, achieves excellent results on the first epoch, and only gets better.

Learning Rate Finder

Training Epochs

Why Google Cloud Functions?

My intention has always been to run model inference on the Raspberry Pi CPU, which is possible now that PyTorch 1.8 supports arm64 builds. One little problem with this plan: There’s a bug in the preprocessing pipelines in the arm64 builds for torchvision. I have invested a bit of time finding this bug’s cause, but it’s trickier to isolate than I expected. Coordinating experiments on two different platforms slows things down a lot, and it’s doesn’t appear to be the result of a single layer or preprocessing operation. Until someone corrects this bug, I get junk predictions on the RPi4.

I need to run inference somewhere else in the short term, so why not the cloud? I’m most familiar with AWS, so that’s the obvious place to turn first. I didn’t want to pay for an always-on x86_64 SageMaker endpoint or similar solution, but Fast.ai, Pytorch, and friends are too large for AWS Lambda functions.

After a little research, I found out that Google Cloud Functions do not have the same strict disk size requirements as AWS lambda functions. It appears Google will automatically build a docker image with all my required packages just fine and execute this function with minimal latency. Best of all, for this use case, nearly everything about using Google Cloud Functions falls comfortably within the free tier! I spend about five cents a month for storage, and that’s it.

Like the earlier code snippets, getting the cloud function up and running doesn’t take too much:

import base64

from fastai.vision.all import *

from google.cloud import storage

import numpy as np

# Download model artifact to /tmp

storage_client = storage.Client(project='birbcam')

bucket = storage_client.get_bucket('birbcam')

blob = bucket.blob('models/birbcam_prod.pkl')

blob.download_to_filename('/tmp/birbcam_prod.pkl')

learn = load_learner('/tmp/birbcam_prod.pkl')

def model_inference(request):

"""Responds to birbcam model HTTP request.

Args:

request (flask.Request): HTTP request object.

Returns:

model prediction dictionary for the passed image

"""

request_json = request.get_json()

if request.args and 'b64_img' in request.args:

img_data = base64.b64decode(request.args.get('b64_img'))

elif request_json and 'b64_img' in request_json:

img_data = base64.b64decode(request_json['b64_img'])

else:

return "Bad request!"

img = np.asarray(Image.open(io.BytesIO(img_data)))

pred = learn.predict(img)

labels = pred[0]

confidence = pred[2]

result = {

"labels": list(labels),

"confidence": list(zip(list(learn.dls.vocab), confidence.tolist()))

}

return resultWhy a Raspberry Pi and an Old/Bad Webcam?

I’m using the Raspberry Pi because I buy tech toys and then retroactively justify the purchase somehow. I use the old webcam simply because I had it lying around. I also want the web app for this project to run locally on my LAN rather than online. The camera overlooks my street, and one could theoretically use it to surveil members of my community. The internet can be a messed up place, and some of the folks on it scare me. The last thing I want is for someone to use the Birb Cam for nefarious purposes.

Why Flask?

Lately, I have enjoyed Streamlit as my go-to solution for building data-driven web apps since it makes it so easy. I don’t use it here because Streamlit is just not great for CRUD (Create Read Update Delete). It’s not impossible, but it requires some cleverness with caching and feels very hacky. I need CRUD for model evaluation, so another solution is required. Historically I have used Django, but in this case, I think it’s overkill. I have a one-table database and don’t need a sophisticated ORM (Object Relational Mapping). For this project, Flask is just right! Like Streamlit, it’s still straightforward to use, but it has plenty of flexibility to allow for just about any design pattern.

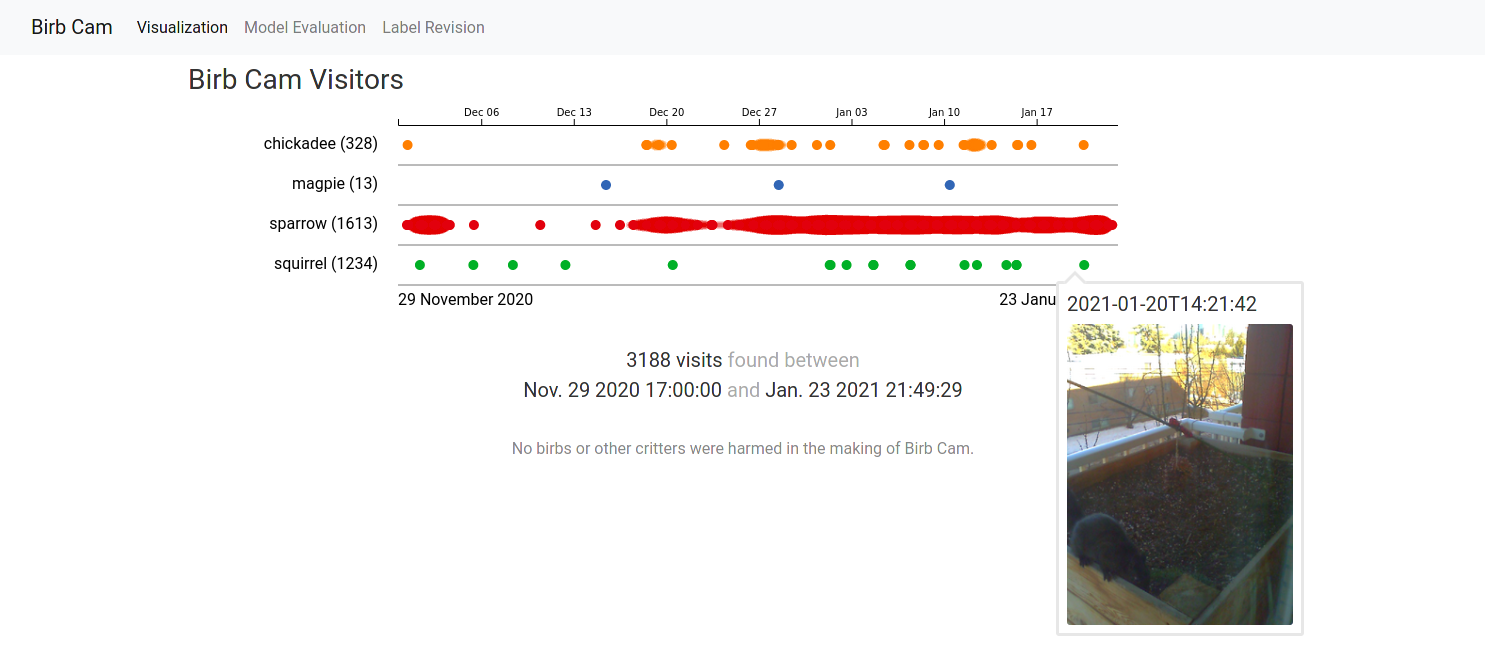

Serving Model Results

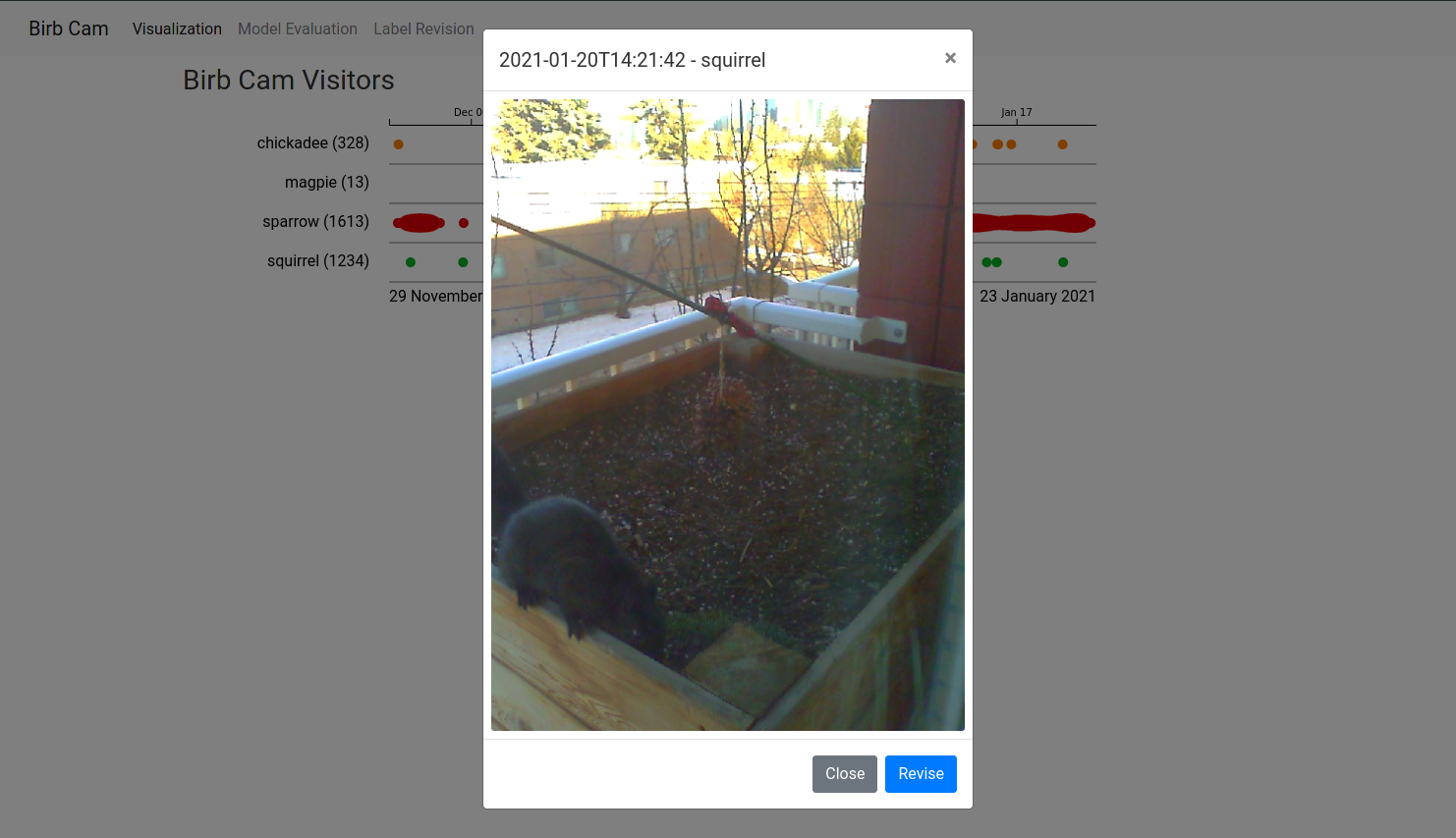

Presenting the model results is accomplished using Flask, with a simple REST API to serve the data and images. The data feeds into a D3 based visualization using the open-source JavaScript library EventDrops kindly shared by the team at marmelab. It’s nearly the exact visualization I imagined building, just with more features! No sense in building my own worse version for this project when the open source community already has me covered! Getting tooltips to preview each image captured required only a little extra JavaScript:

A little more JavaScript and Bootstrap facilitates displaying the full-sized image in a modal when the user clicks on a data point.

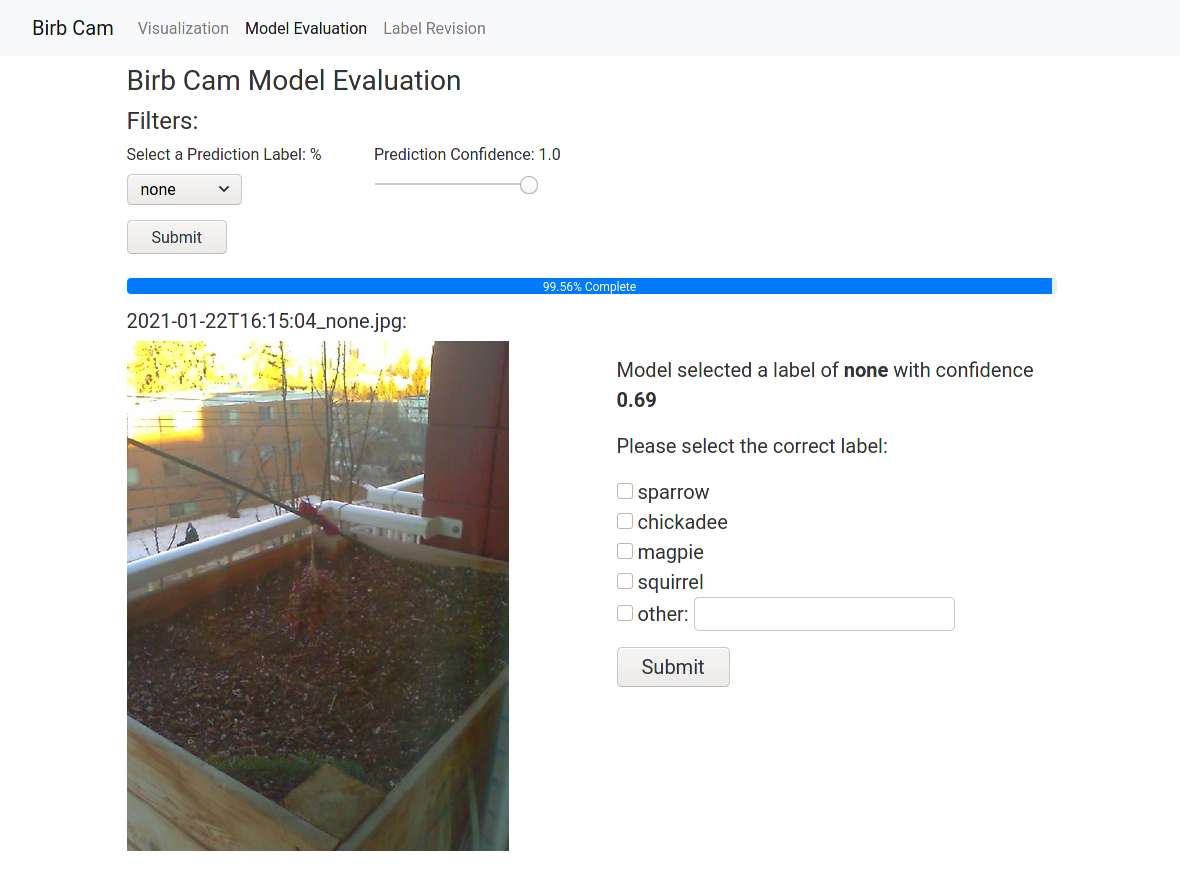

The web app does more than visualize the data; it also allows for the manual evaluation of the labels predicted by the model:

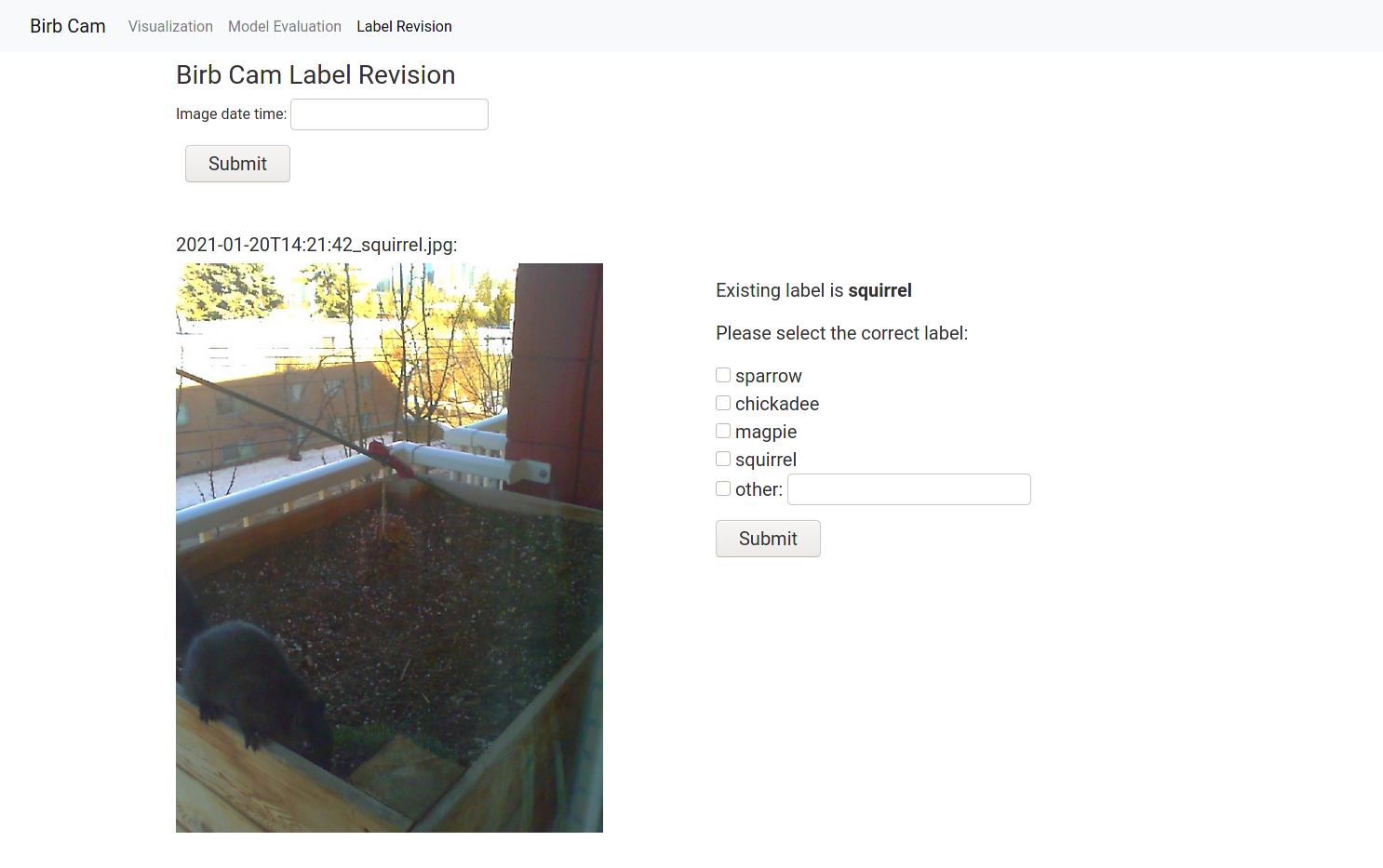

And it provides the ability to revise these labels in the event of a mistake:

So far, I have learned a lot of interesting things with the Birb Cam. I have discovered that the birds and squirrels don’t always show up every day but have surprisingly regular schedules when they do. I also repositioned the camera for less backlighting and discovered that my street has way more traffic than I ever expected. I have also found out that I get a lot of glare on the window from my TV, and it’s hard to prevent this from triggering the change detection between sunset and dusk. I’m excited to collect more data, dig into the patterns that emerge, and see how they change with the seasons. The Birb Cam has been a great pandemic project, and while I’m not sure I’m much of a bird watcher, I hope to maintain and keep the Birb Cam running for quite a while yet.