Arduino: Super Graphing Data Logger

Sections:

Introduction

What is the Super Graphing Data Logger (SGDL)? It is an Arduino project that integrates data logging and the graphing of this data online using little more than an Arduino with the appropriate shields and sensors. It differs from similar projects in that it doesn’t require a separate server or system to collect the data or to run script for the actual plot. Between the Arduino and the user’s browser, everything is taken care of.

If you just want to dive right in, the code is now posted on GitHub: https://github.com/evjrob/super-graphing-data-logger

Some time back I came across this neat javaScript based library for plotting and graphing called Highcharts JS. It didn’t take long for me to realize that charting with javaScript is very convenient for projects in which the server is limited in it’s capabilities, such as when using an Arduino with the Ethernet shield. Since the user’s browser does all the heavy lifting, the Arduino only needs to serve the files which is something it is perfectly capable of. This is especially true now that the Ethernet and SD libraries included in 1.0 support opening of multiple files simultaneously amongst other things. Thus the use of Highcharts allows us to create beautiful interactive charts based on data logged by the Arduino using nothing but the Arduino (and your browser, and a public javaScript CDN).

The Results

The best way to appreciate the final product is to actually play with it. While I’m not going to open up my home network and Arduino to the big wide internet, I have mirrored the pages and datafiles it produces on the webhost I used for my Has the World Ended Yet? project. You can find them here. These won’t be updated with new datapoints like the actual Arduino version will be, but they should at least give a fair impression of how the project looks and feels without the need to actually implement it.

For those who are unsure what they are looking at, I’ll offer a quick interpretation:

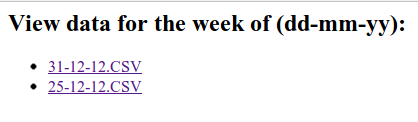

The list of data files available for graphing.

Going to the above page, we see that we are presented with a very basic list of the data files that can be selected from. Clicking any of them will cause the graph for that datafile to be loaded (much more quickly than the Arduino can manage).

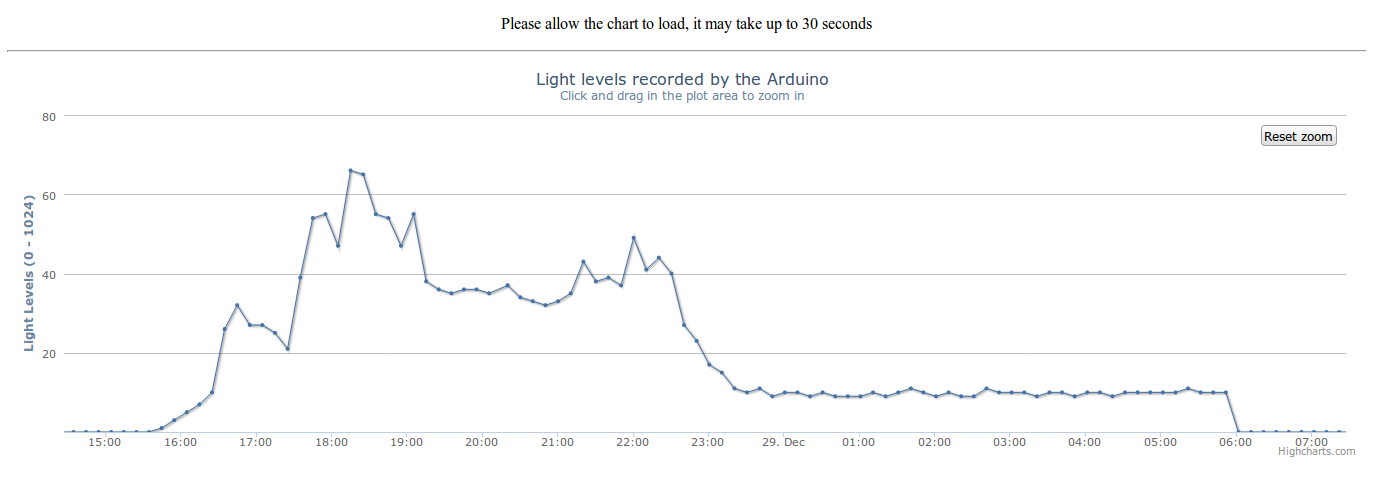

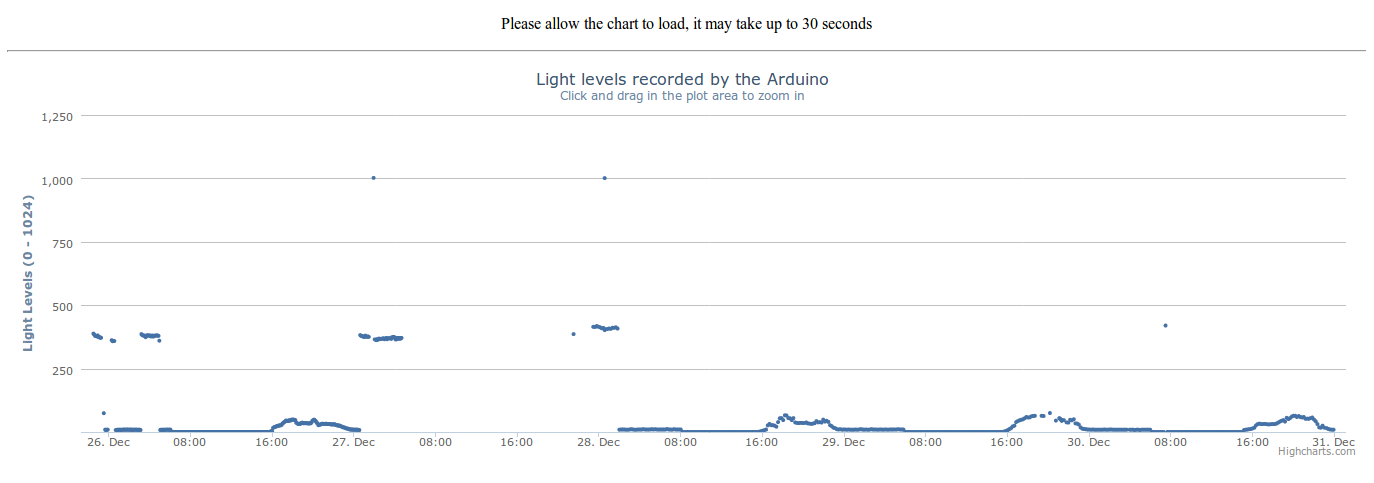

This chart for the 25-12-12.CSV file is already complete, and won’t have any new data added to it in the future, because the files for subsequent weeks have already been made. There is a lot to see though. The two data points that are at 1000 on the y-axis are from when I pointed a bright flashlight directly at the photo sensor. All of the data points between 300 and 400 on the y-axis are the result of the basement lights being on. The abnormally large gaps in the data are periods when the Arduino was powered off because I was still tweaking and developing it. Finally, the short humps that occur everyday are the result of natural light coming through one of the basement windows. By zooming in on one of them, we can see even more detail:

The first thing we notice is that the levels rise from zero to about 65 before falling and levelling out at close to 35 for two hours. This is followed by a another small increase before it ultimately decreases down to a value of ~10 where it levels out. That middle valley where the light levels are equal to 35 is due to the shadow cast on the basement window by our neighbour’s house to the south of us. The levelling out of the light intensity at 10 after all the daylight has disappeared is because a light out in the hallway is usually on in the evening. It is eventually turned off for the night, causing the light levels to drop to zero where they will usually remain until the next morning. I must admit, I’m impressed that the cheap $1.00 photoresistor is capable of capturing this level of detail, and that these trends are so easily interpreted from the graphs.

How to Make One For Yourself

All of the code below is now conveniently hosted on GitHub (https://github.com/evjrob/super-graphing-data-logger) so you no longer need to copy and paste it if you don’t want to.

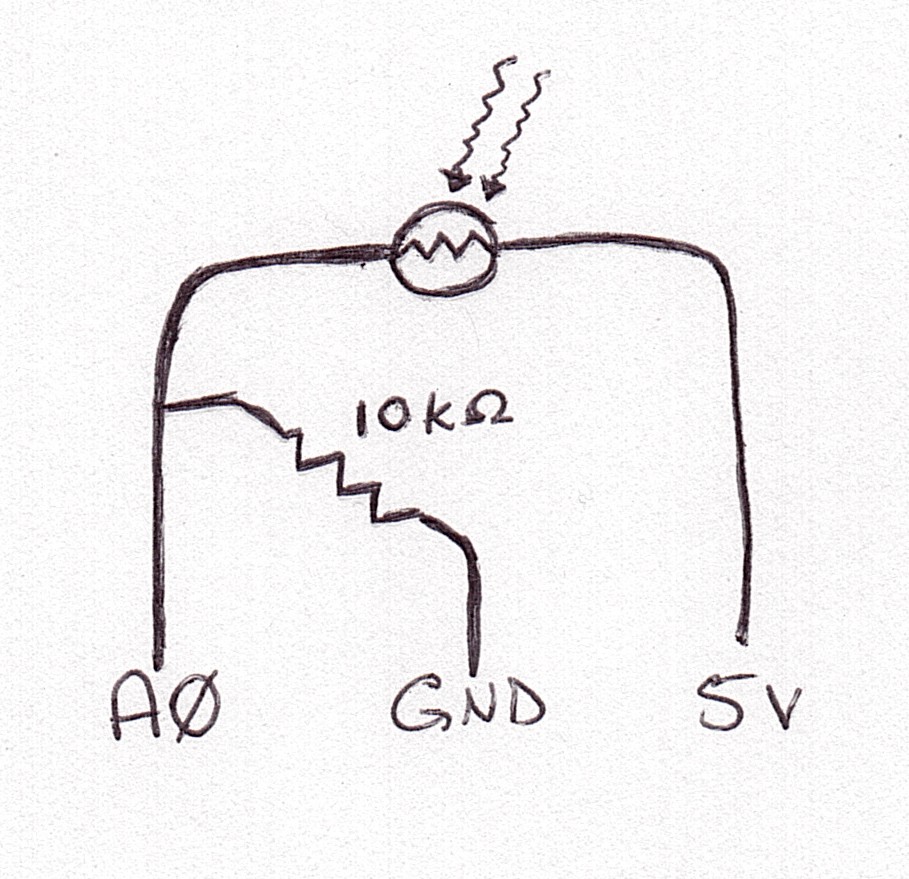

To replicate this project, a few things are necessary. You’ll obviously need an Arduino capable of connecting over Ethernet and storing files on an SD card. In my case, this is achieved through the use of an Uno with the Ethernet shield. Presumably an Arduino Ethernet model will also work fine, though I have not personally tested it. Other non official Ethernet shields and SD card adapters may also work if they use the same libraries, though I make no guarantees. For the more adventurous, it may be possible to adapt my code to achieve the same functionality using a Wifi shield. You will also need a data source of some sort. For my project I chose to use a very cheap photoresistor, which I rigged up on a small perf board to plug directly into the 5v, gnd, and A0 pins of my Arduino (or more precisely, the headers on the Ethernet shield). It is set up in such a way that the minimum recordable light intensity is zero, while the maximum is 1024.

The pins on the male headers don’t quite line up, so I intentionally used extra long ones and added a slight S-curve to the one that goes to A0. This can be seen in better detail above. For those who are interested, the circuit is very simple:

Before we get started, we need to make sure our SD card is good to go. It should be formatted as a FAT16 or FAT32 filesystem, the details of which are available on the official Arduino website. Once that is done, we need to ensure two things are present in the root directory of the card: the HC.htm file, and a data/ directory for our datafiles. The data directory is easily made with the same computer that was used to format the card provided one has an SD card reader of some sort. The HC.htm simply consists of the following code:

https://gist.github.com/evjrob/a221604eb37a282f6fd108921cf5df5e

You will need to edit this file first to make sure it points towards the preferred location of your highcharts.js files. You can leave this as the public CDN: http://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/highcharts/2.3.5/highcharts.js, change it to point towards your own webhost, or it can even be on the Arduino’s SD card (this will be slow). It is not necessary to create a datafile before hand, the SGDL sketch will take care of that when it decides to record its first data point. Before we get that far though, it is necessary to make sure we have configured the EEPROM memory for the SGDL sketch. This is very easily accomplished using a separate sketch, which I have called EEPROM_config. This sketch (along with SGDL itself) requires an extra library called EEPROMAnything, which needs to be added to the Arduino’s libraries folder wherever one’s sketchbook folder is. While you’re at it, you should also add the Time library which we need for SGDL.

https://gist.github.com/evjrob/88f79dbafea0970ea3faa10685c70687

I have intentionally commented out the write line so that no one writes junk to the EEPROM by accident. While the EEPROM has a life of ~100,000 write cycles, I’d rather not waste any of them. Please review the sketch carefully and ensure you’ve adjusted it accordingly before uploading it to the Arduino. The most important thing is to ensure that your newFileTime is something sensible (in the near future most of all).

Now that that’s all taken care of, we’re ready to get SGDL all set up! The code will need a few adjustments for your own specific setup, mostly in regards to the Ethernet MAC and IP addresses. I trust that anyone making use of this code already knows how to configure their router to work with the Arduino, and that they can find the appropriate local IP address to update this sketch with. You may also wish to change the timeserver IP address to one that is geographically closer to yourself.

I currently have my code set up to make a measurement every 10 minutes, and to create a new data file every week. You are welcome to change those parameters, just be aware that the current data file management names files using a dd-mm-yy.csv date format, so the new file interval should be at least 24 hours. Another concern, is that the shorter the measurement interval and the longer the new data file interval is, the larger the files will be. Because the Arduino is not especially powerful, this will have consequences for the loading times of each chart.

https://gist.github.com/evjrob/9b75503a534497c2ef585e98436db331